Originally posted at the Chronicle of Philanthropy.

Imagine this. Your gala is three weeks away, and even accounting for last-minute registrations, you are well below target. You review the list of table captains. The poorest performers? Five of your board members. Three of them aren’t even hosting a table.

You fight the urge to rant and, instead, create a short video highlighting everything the board needs to know to get the word out and increase attendance. You share it with the full board. Separately you ask the board chair to hit ‘reply all’ with an encouraging message to other trustees to recruit attendees.

Four hours later, no responses. The problem: You have a bad board. You’re not alone.

A few years back, Stanford University joined forces with BoardSource and GuideStar to survey nonprofits’ board members about their boards. The picture is startling and probably reflects some serious underreporting by participants:

Almost half (48 percent) do not believe that their fellow board members are very engaged in their work, based on the time they dedicate to their organization and their reliability in fulfilling their obligations.

What’s most surprising is the degree to which executive directors and staff leaders are in denial about the root of board problems. You might blame your board chair for not holding members accountable. You might blame the nominations committee for recruiting members who don’t care. You’re right to be angry, but you’re wrong about why.

The real problem? It’s you. Across the sector, executive directors and key leaders are not holding up their end of the bargain. It is your job — and the job of every staff member at your organization — to be in the business of stoking your board’s passion, the “pilot light.”

Anyone responsible for board recruitment should identify new members who, first and foremost, are in love with the organization. Skills can be learned, but passion has to be in the DNA. Recruitment efforts must give first priority to candidates whose “pilot light” for your cause is bright. When a board member has that kind of passion, you can feel it.

You won’t hit 100 percent all the time, but most of your board members should arrive with their lights shining. Staff leaders tend to think these bright lights just magically stay bright. They don’t.

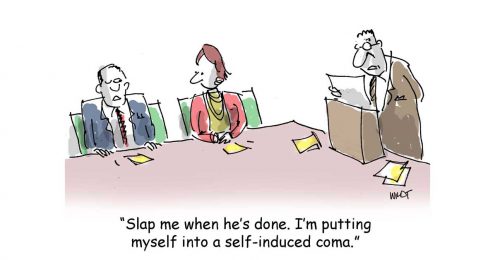

“Dim bulb” boards govern poorly; they care less. Board members check their phones at meetings while staff members are sharing successes. They focus on cutting expenses when revenue projections are off. They are responsible for more nonprofit leaders returning calls to recruiters than they will ever know.

How to Reignite Your Board Members

To engage trustees, I use a simple equation when coaching executive directors, which creates a more productive partnership and equips trustees with the enthusiasm and tools they need to become real ambassadors:

The formula: Inform + Engage + Enrich = Ignite

Most board members will tell you that they are informed. But as a nonprofit leader you need to take two other critical steps to create vocal and visible ambassadors for your cause ― the kind of ambassadors whom those you serve need and deserve.

For example, last year I worked with an equine-therapy program that offers the benefit of horseback riding to kids on the autism spectrum. I gave the executive director some tough love: I told her that her fingerprints were all over her disengaged board.

Here’s how we used the formula.

Inform. The information has to “stick” ― no recitation of your board report. Instead, a PowerPoint presentation with only 13 slides, each with a single image of the horses — the real stars of the organization. On every slide, the name of the horse and its “magic power,” such as one horse that is uniquely attuned to anxiety whose healing power helped transform one child. Not only are those board members informed, but now they have personal and powerful stories to tell.

Engage. The topic must tap into what board members bring to the boardroom. For example: The equine-therapy group is considering purchasing an adjacent property. The executive director wants to serve more kids, and the conversation about purchasing the property is big and strategic. So, the director framed the pros and cons to the board, asking questions like these:

- “Am I thinking about this the right way?”

- “If we don’t buy it, who might be our neighbor, and how would that affect us?”

- “If this property weren’t going on the market, would we be looking to expand?”

- “What other questions should we be asking?”

- “What additional information do we need?”

A boardroom of people with the right skills and expertise will add a lot of value to the discussion. And then, when you move forward, the trustees share ownership of the decision, which always leads to more-enthusiastic fundraising.

Enrich. Board members are leaders. Leaders have context and know trends, but they need data. For example, if you are serving kids on the autism spectrum, you need to tell trustees the extent of the problem, expected future trends, and whether the population is growing.

The executive director of the equine-therapy organization has a large network of contacts. Working with her board chair, she extended one board meeting by 30 minutes to allow time for an expert to give a 20-minute presentation with 10 minutes of Q and A. The expert also joined a social gathering afterward. Very few board members left early.

Think of your last two, three board meetings: Did you give your board a bite of any of these three elements of the formula? Were you intentional about how to use a meeting to accomplish any of these things?

Let us know something you are going to try. Big problems require some good thinking. Share yours below.